WHY DID WE UNDERTAKE THIS RESEARCH?

The impact of heroin dependence on individuals is often long term with significantly poor health and quality of life. Heroin is also a significant problem for our health system and in 2011-12, more people sought treatment for heroin use in Australia than any other illicit drug (n=65,952) (AIHW 2012). Yet, there are very few long term studies anywhere in the world to help us understand the challenges faced by people addicted to heroin. An understanding of the long-term health and social impacts of heroin dependence, mortality, criminal involvement and mental health are critical in improving health outcomes. Yet we are frustrated in improving outcomes for individuals by a lack of information and data.

WHAT IS ATOS?

In 2001, a team of researchers from the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC) tried to address this gap in our knowledge. The group of addiction researchers started the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS) to answer the questions

- How persistent is heroin dependence?

- How chronic is heroin dependence?

- It heroin dependence a relapsing condition and if so when and can we predict those relapses?

Maree Teesson, Shane Darke, Michael Lynskey and Joanne Ross conceived the study and sought the first funding for the study in 2001. Katherine Mills was one of the first researchers on the study and a current investigator. ATOS was developed as a longitudinal cohort study of 615 entrants to treatment for heroin dependence1. The cohort was originally followed up at 3 months2, 12 months3, 24 months4 and 36 months5. A range of scientific papers were prepared on the first three years of follow-up with detailed outcomes for the cohort6-14. In 2011 we were successful in obtaining NHMRC and government funding to extend the study to 11 years. This is now one of the longest running follow-up studies anywhere in the world. The participation of the cohort and the amazing skills of the research teams have meant that we now have a chance of closing the knowledge gaps.

Members of the original ATOS research team (from left to right): Alys Havard, Joanne Ross, Shane Darke, Katherine Mills, Kate Hetherington, Maree Teesson and Anna Williamson.

WHAT DID WE DO?

In NSW, 615 participants were recruited from 19 agencies treating heroin dependence in the greater Sydney region. The agencies comprised methadone/buprenorphine maintenance agencies (MT), drug free residential rehabilitation agencies (RR) and detoxification facilities (DTX). A group of heroin users not currently in treatment (NT) were also recruited from needle and syringe programmes. The ATOS baseline sample was predominantly male, in their late twenties and had been using heroin for a decade. Few were in full-time employment, and there was extensive prison experience1. Almost all (90%) had previous treatment histories.

WHAT DID WE FIND AT FOLLOW UP?

Contrary to expectations that it would be next to impossible to follow up the original cohort at 11 years, the majority of the cohort (over 91%) was located. 431 individuals were re-interviewed (70%), a further seven (4%) were incarcerated and 63 (10%) were deceased. The follow up rates compare favourably with the earlier points: 3-months (89%), 12-months (80%), 24-months (76%), and 36-months (70%).

WHAT WAS THEIR TREATMENT EXPOSURE?

Treatment exposure over 11-years was extensive. Of those interviewed at 11-years, 47% were currently enrolled in a treatment program, including 60% of males and 40% of females. By follow-up, the entire baseline non-treatment group had experienced treatment for heroin dependence over that period, and 37% were currently enrolled in treatment. Overall, the cohort had received a median of 1,465 treatment days over 11-years, over a median of 4 different treatment episodes.

There was substantial movement between treatment modalities over time. Of those who commenced in maintenance therapy (MT), 36% had a subsequent enrolment in detox (DTX) and 28% in residential rehab (RR). Similarly, of those who commenced in DTX, 70% had subsequent MT and 49% enrolled in RR. Finally, of those who commenced in RR, 67% had subsequent MT experience, and 55% a subsequent DTX.

HAS HEROIN USE CHANGED?

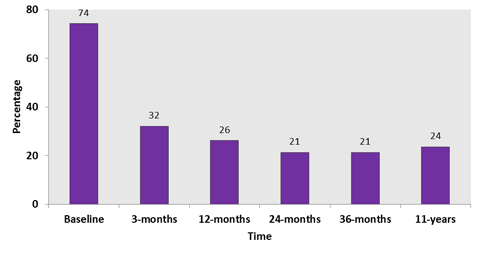

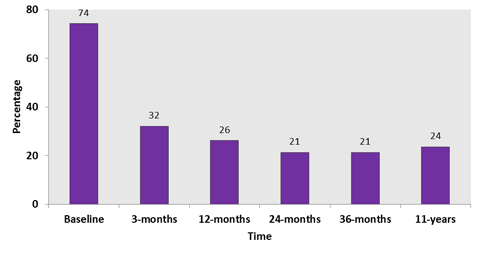

The positive effects of treatment were demonstrated in the substantial reductions seen in heroin use over 11-years (Figure 1). Daily heroin use had declined sharply from 80% at baseline to 24% by 3-months, declined again to 17% at 12-months, where it remained fairly stable to 36-months. By 11-years however, daily heroin use had further declined to 4%. Current heroin abstinence was 49% by 3-months, and increased to over half of the cohort at all subsequent follow-ups. By 11-years, three-quarters of this group of long-term heroin users were currently heroin abstinent.

Figure 1: Heroin use in preceding month

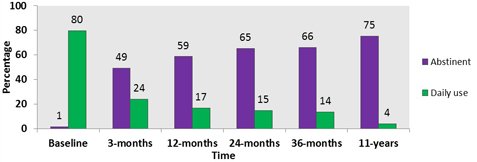

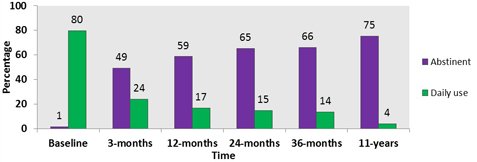

As with heroin use, there was a substantial reduction in heroin dependence over the follow-up period. Whilst almost the entire cohort was heroin dependent at baseline, by 11-years this had reduced to 15% (Figure 2). Similar to heroin use, the sharpest declines in heroin dependence were evident from baseline to 3-months. In contrast however, the use of other drugs remained high throughout the follow-up period. Whilst there was a reduction in other drug use from baseline to 36-months, this was not maintained to 11-years, which saw an increase from 77% at 36-months, to 85% at 11-years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Past month heroin use, dependence and other drug use

HAS THERE BEEN A CHANGE IN RISK-TAKING BEHAVIOURS?

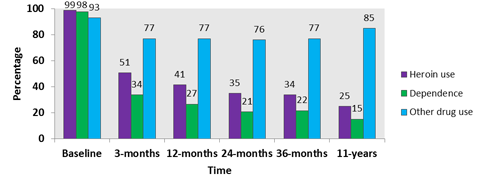

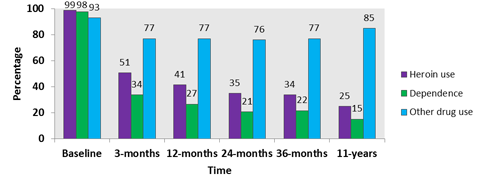

As with heroin use and dependence, daily injecting declined dramatically over the first 3-months, declining still further at the 12-, 24-, and 36-month follow-ups (Figure 3). By 11-years, only 10% were injecting daily, compared to 79% at baseline. Borrowing used syringes declined from one in five of the cohort at baseline to approximately one in forty by 11-years. Critically, in terms of risk of death, annual heroin overdose rates declined over each subsequent year. In the year prior to the commencement of ATOS, 24% had overdosed, compared to only 5% at 11-years.

Figure 3: Risk-taking behaviours at baseline and 11-years

Note: 3mth follow-up not applicable for annual overdose rate.

Overdose rates had declined, but overdoses were still occurring. By 11-year follow-up, 68% of the cohort had overdosed on at least one occasion, with the cohort reporting a total of 1,284 different overdoses. An overdose in preceding year was reported by 5%, representing 12% of those who had used heroin in that period.

Of the 21 cohort members who had recently overdosed, almost all (20/21) had recently had done so previously. Importantly, 19/21 were not enrolled in treatment at the time of their most recent overdose. Consistent with earlier work on the role of other drugs in causing heroin overdoses, those who recently overdosed had higher levels of polydrug use. Specifically, they had higher levels of opiates other than heroin, benzodiazepines, methamphetamine and cocaine.

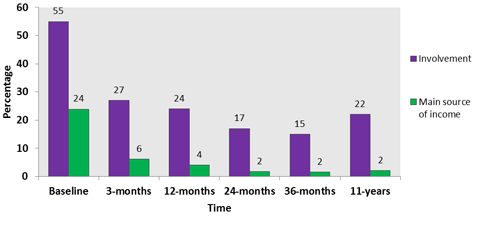

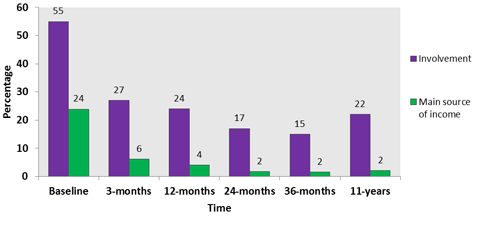

HAS THERE BEEN A CHANGE IN LEVELS OF CRIME?

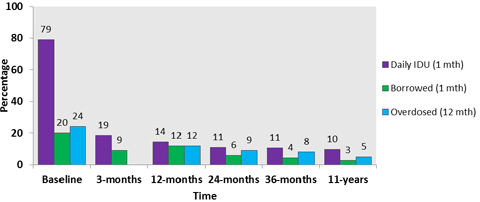

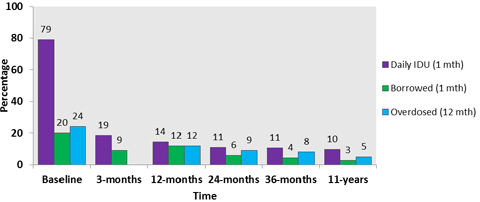

Consistent with the large declines in heroin use and injecting, levels of criminal involvement declined from baseline to 11-years. As with heroin use and dependence, the sharpest decline occurred at 3-months. The reduced impact on society is evident by the fact that 55% had committed crime in the month prior to the commencement of ATOS, compared to 22% at 11-years. Although there was a slight increase in criminal involvement between 36-months and 11-years, it was not statistically significant. Importantly, at baseline, almost one-quarter of the cohort indicated their main source of income was obtained from criminal activity. At 11-years, this had dramatically reduced to just 2.1% (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Proportions committing crime, and reporting crime as main source of income in the preceding month

HAS THERE BEEN A CHANGE IN PSYCHOLOGICAL HEALTH?

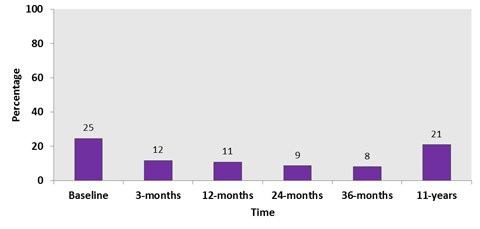

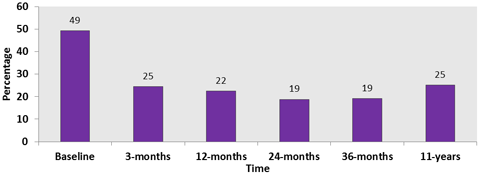

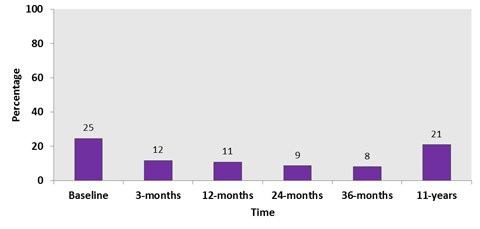

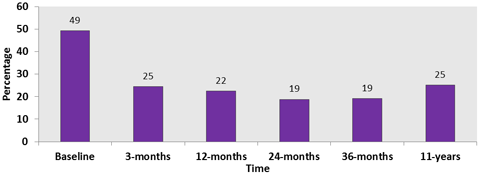

Although there were substantial and sustained declines in heroin use and crime, the psychological health of the cohort had substantially worsened (Figures 5 and 6). Whilst the overall mental health of the cohort had improved dramatically from baseline to 36-months, by 11-years, general mental health had substantially declined and remained very poor compared to the general population (Figure 6). At baseline, 49% were categorised as having severe mental health problems compared to 19% at 36-months, and 25% at 11-years. Despite improvements over the course of the study, poor psychological health remained a problem for large proportions of the cohort.

At baseline, a quarter of the cohort had a current diagnosis of major depression (Figure 5). This proportion was halved by 3-months, and declined at each subsequent point to 36-months, where 8% met criteria for a diagnosis. However, by 11-years, current depression had sharply increased, to the point where one in five met criteria for current major depression.

More than one third of the cohort had a diagnosis of lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at baseline, with almost one third of the cohort having experienced symptoms in the 12-months prior to the commencement of ATOS. At 11-years, one-fifth of the cohort had a diagnosis of current PTSD, with 74% experiencing a trauma at some point during the follow-up period.

Figure 5: Current major depression diagnosis

Figure 6: Mental health (severe disability)

HAS THERE BEEN A CHANGE IN PHYSICAL HEALTH?

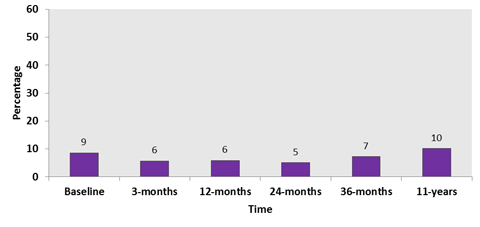

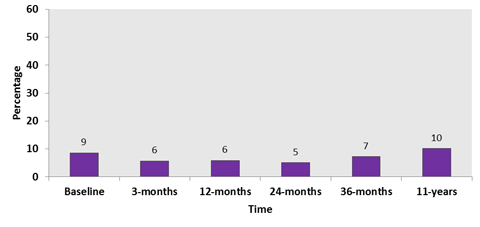

The physical health of the cohort at baseline was well below the population average, although not nearly as poor as mental health. Whilst overall physical health had improved from baseline to 36-months to the point where the cohort paralleled the health of the general population, by 11-years, physical health had substantially declined. At baseline, 9% were categorised as having severe physical disability (Figure 7), which reduced to 7% by 36-months. By 11-years, however, more than 10% of the cohort were categorised as having severe physical disability, which was not only higher than the previous follow-up, but higher than baseline levels.

A decline in injection rates was accompanied by a marked reduction in injection-related health problems. As with heroin use and dependence, the sharpest decrease occurred in the first 3-months, but there were further declines at subsequent follow-up points. While 74% had injection-related health problems at baseline, reflecting the high rates of daily injecting, this had dropped to 24% by 11-years.

Figure 7: Physical health (severe disability)

Figure 8: Current injection-related health problems